March 2005

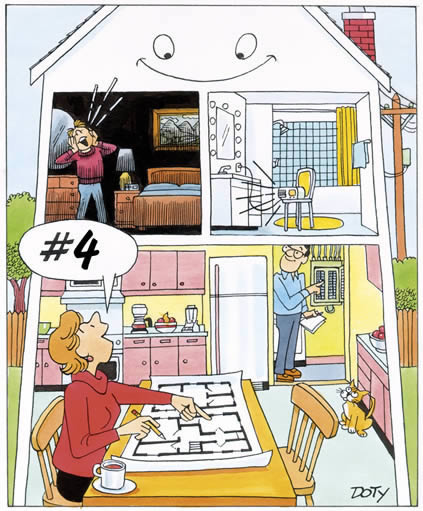

You don't have to be a professional electrician to diagram the electrical wiring in your home - but why would anyone want to do that?

Actually, there are many good reasons. Knowing the pattern of your home's wiring circuits and how your electrical service panel is organized can be a big help when a circuit breaker trips or a fuse blows. It's also important to know if the wiring in your home is keeping up with your lifestyle. Finally, whether you know it or not, you're in a good position to "optimize" your system if your pattern of electrical use isn't well-matched to your house's circuitry. More about that later.

People who live in older homes should be especially attentive to their wiring. Today Americans consume nearly five times as much electricity per household as they did in the 1950s. If your home was built back then, or earlier, it may still have the original wiring - inadequate by today's standards.

Even a newer home could have insufficient wiring. Builders don't often build for above-average power usage. And home electrical use will only increase in the future. For all these reasons, and more, you need to take inventory of your house's wiring.

Getting Started

Begin by switching off one circuit breaker or removing one fuse at the electrical panel in your home. Next, determine which plug-in receptacles (or outlets, as they're commonly known) and which switches don't work when that circuit is off.

Outlets can be tested with a low-cost multimeter or an electrician's test light, or you can simply use a night-light or lamp. Be sure to test both receptacles of duplex (double) outlets, since one half might be on a completely separate circuit. If so, make note of it; this could be a dangerous situation. The second half of the outlet could also be connected to the same circuit through a switch in the room, for convenience. Part of the mapping process is to note what your switches control.

Finally, be sure to note which outlets are GFCIs (ground-fault circuit interrupters). These are there for your protection and can be identified by the presence of two buttons marked Test and Reset.

If you're working alone, you can save some steps if you plug in a loud radio, then turn off each of the breakers or remove the fuses, one at a time, until the music stops. This will identify which circuit you're dealing with. You can then map that circuit by testing nearby outlets and switches.

Next Steps

Test results should be collected - circuit by circuit - and entered into a table. Each outlet or light switch in the house should be uniquely identified in the table. Record the amperage rating for each circuit (identified on the breaker or fuse) as well.

If practical, also record the gage (diameter or thickness) of the wiring in each circuit, typically marked on the plastic outer jacket containing the wires. If it's 14 AWG, the circuit should be protected by a breaker or fuse no larger than 15 amps. If it's 12 AWG - 20 amps at most. If it's 10 AWG (such as most clothes-dryer circuits) - 30 amps maximum. The importance of proper breaker and fuse sizes cannot be overstated. If they're not correct, they should be replaced at once.

Depending on the size of your home and the extent of the wiring, you may have anywhere from a few to 10, 20 or even 40 separate branch circuits. Generally, more circuits means less chance that any one circuit will be overloaded.

It may come as a surprise that ordinary homeowners can actually do something to improve or "optimize" their electrical systems. Depending on your level of competence - and your local laws - you may be able to solve some of the problems revealed in your mapping.

For example, an overloaded circuit can be divided into two circuits by adding an extra wiring run. This not only makes your home safer, but it will also reduce or eliminate tripped breakers or blown fuses. Replacing a broken light switch, or an outlet that needs to be upgraded, is a fairly simple do-it-yourself job. (Don't forget to turn off the power first.) Replacing standard outlets with GFCIs (now required in kitchens, baths, basements and other wet locations) may require the expertise of an electrician.

One caveat: If you're not sure you can do electrical repairs, and do them right, call a qualified electrician (as opposed to your next-door neighbor). And now, with your home wiring map, you'll have a better understanding of your system and will be able to talk knowledgeably about any upgrades needed and save a lot of time.

For more information, visit the CDA's Building Wiring section. ![]()