The Combustible Side of Copper Art

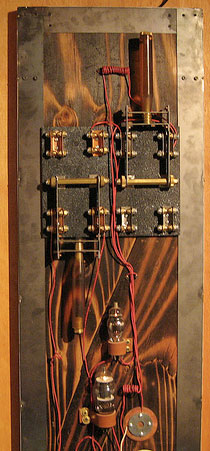

High voltage display panel with brass and copper findings.

High voltage display panel with brass and copper findings.Photograph courtesy of Rusty Oliver

Rusty Oliver does a lot more than play with fire. More than a decade ago, Oliver delved into industrial art, testing out the tantalizing persuasion of flames after taking inspiration from the Petaluma, California-based Survival Research Labs, known for its less than ordinary approach to machining and metals.

Well-versed in hearing puns about his name, he often opens up with the line, "My name is Rusty, and I work with metal. If you have a hard time remembering that, I'm going to take it as some kind of indicator."

It's far from coincidental that Oliver's interactive art shows are entwined with metal, just like he is on a daily basis.

In 1997, Oliver opened a collective known as the Hazard Factory, which he relocated to its current 2,200-square-foot Seattle, Washington space five years ago.

King County's Hazard Factory is comprised of about 30 members who are heavily involved in an annual power tool drag race in the region, with the event taking planning and preparation from all of them and other volunteers throughout a year's time.

Oliver also teaches welding, metal-casting and fabrication classes, when he isn't off making friends with flames.

Surprisingly enough, in his years of perfecting fire art through copper, steel, and aluminum structures, never once has he burned himself in his process. And, although regional fire departments originally saw Oliver as a threat, they've recently been recognizing more value in his art and the benefit of appreciating their common ties.

High voltage display panel with handmade copper and brass switches and voltage fixtures.

High voltage display panel with handmade copper and brass switches and voltage fixtures. Photograph courtesy of Rusty Oliver

Today, Oliver uses perforated copper pipes, but in the past few years, he's also stirred into experimenting with high voltage and its effects on an open flame with copper electrodes to conduct currents while playing a Chemical Brothers song, seeing the flames reacting and bouncing to the sound.

"Lately, I've been casting Nerf guns and turning them into flamethrowers, implementing a copper manifold, while the propane propels fire almost four to six feet outward." Oliver says, "The form of the object is really elaborate. They look like these insane, crazy, giant science fiction weapons. But they seem like something that would much rather shoot an enormous ball of plasma or an open flame rather than a soft Nerf ball. This is what a Nerf gun wanted to be when it grew up. It's funny, but it's also a comment on the object and the role it plays in society."

He also builds aluminum, steel, and copper-constructed wings for fire performers and is newly casting bronze, too.

"Copper is nice because it's a very malleable, easy material to work with, it's reasonably tough, and it's really pretty," Oliver says. "I usually have 200 pounds of it on hand in sheets and washers. It has a timeless quality."

For the copper element of his live sculptures, Oliver sources his samplings from Alaskan Copper & Brass Company in Kent, Washington.

He's brought his fire art into public art walks in both Olympia and Seattle, along with Amsterdam's Robodock Arts Festival, with its focus largely on industrial arts.

In the past, when not spending 50 hours a week in the Hazard Factory and teaching an industrial-based sustainability and green manufacturing course at Seattle Central Community College, Oliver did commissions working as a personal instructor at people's homes, showing them the fragile yet fruitful way of laboring artistically with fire.

"Basically, everyone's a pyromaniac," Oliver concludes. "I just chose to go pro."

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Jimenez Sculpture: The Beauty Is in The Copper Detail

- Copper in the Air

- Greg Wilbur: Using An Ancient Process to Create Contemporary Artworks

- The Combustible Side of Copper Art

- Large Salvador Dali art collection on display in Austin