Thinking in Metal: Sculptor Richard Hunt

Sculptural Improvisation #2, welded bronze, 1991

Sculptural Improvisation #2, welded bronze, 1991Photograph courtesy of Richard Hunt

In April 2009, Chicago-based sculptor Richard Hunt was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center in Hamilton, NJ. The award, and literally hundreds of others, are nice. "It's satisfying to have lived long enough," the 74 year old Hunt says laughing. "I was surprised and elated at the news and it certainly is a career highlight." But even now he seems more attentive on working than getting accolades.

Hunt is a focused man and has been for nearly three quarters of a century.

"It's just like you learn a language, you start to think in it," he says. "I think in metal. The ideas just come to me." He grew up in a family that "appreciated art." To be more precise he says, "My mom was supportive and dad was tolerant."

From his earliest recollection he was always drawing. He did the obligatory posters and scenery backdrops for school plays and by the time he reached the eighth grade he began taking classes at the Junior School of the Arts - part of the Art Institute Chicago - which put him in proximity with "art as it's practiced at a more professional level," he says. "I associated with other people who were similarly inclined," he adds.

As he looks back on his life, he credits the Chicago public schools which offered a year of art and a year of music as part of their curriculum. It was good timing, since in the ensuing years arts in school systems has taken a beating and in some cases been cut altogether. He attended the University of Illinois and the University of Chicago, but eventually received a degree from the Art Institute of Chicago in art education, thinking he might need to hedge his bets and teach if the whole "artist thing" didn't work out.

Richard Hunt at work

Richard Hunt at workPhotograph courtesy of Richard Hunt

He doesn't point to a seminal event that clarified his career path. "There were moments, events that had a cumulative effect that set up my career." He pauses, then recalls something. "Well, a teacher suggested sculpture and once I began working in a concentrated way with the third dimension, I realized that was the dimension I wanted to work in."

His introduction to direct metal sculpture was the result of a 1950s exhibition touring the U.S. entitled Sculpture of the 20th Century featuring works by Picasso, Spanish abstractionist Julio Gonzalez, David Smith and others, where the young Hunt saw firsthand works done in welded metal. It was then that he began a life long affair with abstract expressionism and his work is ripe with examples.

"I was still a student at the time so I took classes in metal works and metalsmithing and developed an approach derived from what I'd seen."

In fact the early works by Hunt, from the 1950s through the 1960s, was done in steel, though he quickly added bronze to his repertoire. "I was interested in the permanence of the material and the historical tradition that bronze represented." He did some teaching and then the opportunities to exhibit came up. He entered exhibitions and won prizes, one after the other. It seemed so easy. "Soon I was making more money from my sculpture than from teaching!" Of course, things are never that easy, but for Hunt, it was an organic flow, one he trusted, which enabled him to focus on his work, not on creating a career.

"The first larger commissioned works I did were in corten steel. In the early 1970s I started to work with fabricated bronze, some copper and brass. I like the direct metal fabrications approach," he says. "There's a relative ease of fabrication, manipulation and longevity and ease of maintenance that's built into the material itself." And as he notes, outdoor public works have to "fend for themselves" he says, therefore brass and steel are a wiser choice.

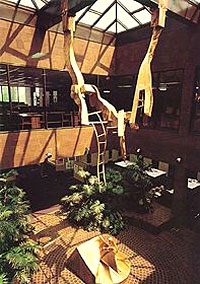

Jacob's Ladder, welded bronze and brass

Jacob's Ladder, welded bronze and brass Photograph courtesy of Richard Hunt

People always want to pin down his "important" works, and even here Hunt is rather elusive. "Works are important for themselves, or a point in your career when you make a breakthrough, in perhaps scale or complexity," he notes. One such piece for Hunt was Jacob's Ladder from 1977, a welded bronze piece for the Carter Woodson Library in Chicago, and a group of pieces in Washington DC in the early 1990s - Build Grow and Growth Columns both set in an urban metro plaza, all from welded bronze. He prefers however not to single out individual pieces.

It is the cumulative work that represents the identity of the artist he believes. "One proceeds along a path, different projects provide the opportunity to take a few steps more along that path." But Hunt has had his share of breakthroughs. He was the first African-American artist, for example, to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1971. His commissions for large-scale public sculptures from Chicago to Atlanta have earned a place for his works in dozens of museum collections. The Cleveland Museum of Art owns numerous drawings and two of his sculptures; a third was commissioned for the Justice Center in downtown Cleveland. Additionally his work is housed in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. and museums in Austria, Israel, Los Angeles and many other major cities. And that doesn't take into account his honorary degrees from Tufts University, University of Notre Dame, Illinois State University, nor the vast number of boards he's served on. And then there are the multitude of fellowships, prizes and awards. These lists alone can fill a small book. No, he prefers to work and let that work speak for itself.

His work has always been known for its graceful fluidity. "That's one of the hallmarks of my personal style," he says. "How a branch is bent by the wind, a wing in movement--all those things are part of the sculptural vocabulary." As he works with welding torches, buffers and chasing tools, his sculptures, formerly hard edged pieces of silicon bronze, begin to morph and assume seemingly liquid qualities. "When they're rendered in metal, the sources are synthesized into a metallic construction," he said. "What starts out as a leaf can become a flame." It is that flexibility which is his delight. Though Hunt still uses stainless steel, he also uses rolled silicon bronze sheet, ranging in thickness from 1/8 to 1/2 inch. His current supplier, German-based CSN Metals is one of the few places that provides the silicon bronze he seeks. He has cast a few large scale bronze pieces, though he prefers the welded metal approach and he is less interested in creating patinas for a visual effect. "I've used some of the color that's derived through heating the material, and some traditional patinas. But my interest is form and space constituting the way I express myself in sculpture, not the surface treatment," he adds.

Currently Hunt is preparing several works for the communities of Flint, Michigan, Newport News, Virginia, and Chicago State University. "A lot of projects I'm doing are related to cities trying to renew themselves and feeling like art ought to be a part of it," he says. And then there will be his one man show at the Robert Bentley Gallery in New York in 2010 consisting of 20 to 30 pieces. Like his seamless welding, Hunt moves easily between commissions and self-generated work, and they both have their rewards and their differences. "Because of the scale of self-generated work, it allows you to concentrate on the doing, rather than the location, budget, size, scope, and logistics of commissioned pieces." In fact Hunt can point specifically to his piece entitled Play in 1967, of welded corten steel that added a new but corollary path for him. "Play, as I look back on it, began what has been a second career for me, that of a public sculptor."

Inside his massive studio, a crowded space where he's crafted art for over 30 years, he's hard pressed to give out words of wisdom. "I don't like to give advice, but I would say, the art world has evolved and changed. There's a very different place to begin a career today then when I began mine. Get a website early," he suggests. He of course made a name for himself the old fashioned way, prior to the Internet and instant acclaim. He simply kept working to his own standard. And now, after 50 years as a sculptor, he takes everything in stride.

"It's been a real delight to have the kind of recognition I've received, not that I wouldn't keep doing it anyway," he says.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Thinking in Metal: Sculptor Richard Hunt

- Shaping the Modern Aesthetic: Emmett Culligan Designs

- The Legacy of Gregorian Copper

- Dick Roberts: From Photography to Metal

- Frick Exhibit Features Copper Daguerreotype Photographs