The issue of lead in drinking water is not new—it's been around for decades, brought to the surface by the dangers its exposure can have on communities as a whole. The latest crises resulting from water quality concerns have only brought it to the front page. The issue goes beyond water quality. As our water distribution infrastructure ages, utilities and municipalities are fighting a losing battle against leaks, changing water supplies, regulatory requirements and plumbing design changes. All of these put pressure on the infrastructure and the utilities’ ability to deliver water cost effectively.

Flint Water Crisis

Flint, Michigan officials switched the city's water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River in 2014 as a cost saving measure. However, the untreated corrosive water caused unsafe levels of lead to leach from aging lead pipes, joints and fixtures into the drinking water. Between six and 12,000 children may have been exposed.

Now, homeowners and city officials across the country are hyperaware of their drinking water quality. High levels of lead in tap water have been found in nearly 2,000 water systems in all 50 states across the country. However, the lack of real lead service line inventories could mean that this estimate is conservative.

Homes built after the 1950s generally have copper pipes but many older home continue to be serviced by unsafe lead pipes (the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986 officially banned the use of lead for drinking water distribution).

Copper tube and fittings have a long history of safely conveying drinking water. No other material has the long-term, proven experience of reliable, leak-free installation in the widest variety of systems and settings, protects the water system from outside contamination in the underground environment and does so with proven life-cycle value.

Water Service Lines

Before the water used for drinking, cooking and bathing reaches the user, it passes through a complex system of pipes, valves and fittings as it is collected, treated and disinfected. After the water leaves the treatment and distribution plant, it passes through large diameter water mains that carry large volumes of water throughout a city or town.

While the water main below street level may be 3-inches, 4-inches or feet in diameter, the water service is typically much smaller—maybe ¾-inch or 1-inch for typical homes, or maybe as big as 2-inches or more for larger buildings, such as hotels.

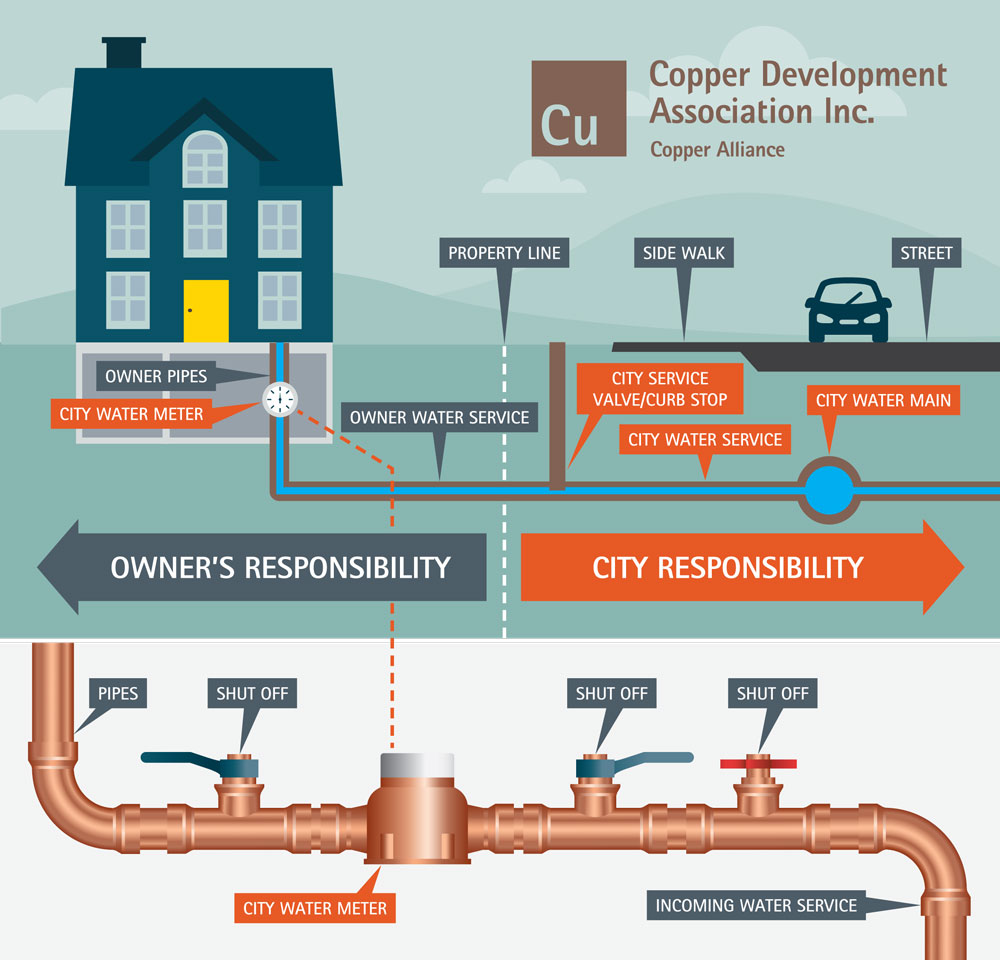

Depending on the municipality and water system, homeowners and business owners may own and be responsible for the entire line from the building to the main; the municipality may own the entire line; or it may be shared ownership. The property line is usually the marker used to determine who is responsible for which portion of the line.

If the water meter is located within the building, a short portion of the water service line may be visible on the upstream side of the meter, however this may not identify what the entire line is made from. If the curb stop can be accessed (usually located near the edge of the street) the piping on either side of the stop may be visible to identify the piping material used. Either way, depending on a number of factors (age not being the least) a service line may have been installed using various materials: lead, galvanized steel/iron, copper or a number of plastics such as PVC, polyethylene, polybutylene and polypropylene.

Full vs. Partial Replacement

Service line replacements can be a big undertaking considering that a recent study in Environmental Engineering Science recommended that lead service lines should be replaced in their entirety. Creating a 'hybrid' system by replacing sections with alternate materials can exacerbate lead leaching—at least in the short-term—into drinking water systems. Municipalities that are considering updating their service lines should replace them entirely with copper in order to help protect the integrity and safety of the water they are supplying. Its long life cycle, combined with its ease of recyclability back to the same metal purity (not downcycled to a lower purity or lesser use) make copper a truly sustainable piping material.

Where is the Lead

Lead was once prized for its longevity and formability, making it the preferred piping material at one time. More than 70 percent of cities in the U.S. with populations greater than 30,000 used lead water lines by 1900. Warning signs began popping up as the health impacts of the ingestion of lead became known. Lead is a serious neurotoxin with severe adverse health effects associated with even very low intake concentrations. To address the problem and reduce the risk of lead exposure through drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (USEPA) instituted stringent requirements on the amount of lead that can be present in drinking water before actions must be taken. While there are many compounds controlled by the Safe Drinking Water Act, the levels at which they are controlled show their relative potential impact on health. Lead is regulated at 15 parts per billion in water, 87 times more stringent than the 1300 ppb allowable for copper.

A 2016 review of the EPA's enforcement data by USA Today revealed nearly 2,000 drinking water systems serving 6 million people in all 50 states have experienced excessive or harmful levels of lead. In fact, 373 of these systems failed repeatedly for excessive lead. Perhaps the best way to eliminate the risk now and for all future generations is to remove and replace all lead service lines from our critical water infrastructure.