The American Folk Art Museum Explores Weathervanes as a Symbol of Classic Americana

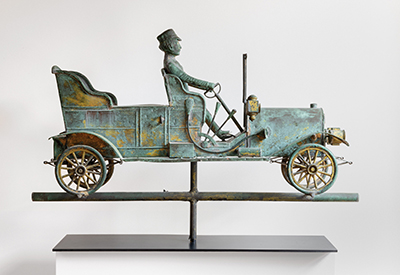

W.A.Snow Iron Works; Touring Car and Driver weathervane. From the

collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren.

Photograph courtesy of Adam Reich.

Weathervanes are among the most instantly recognizable examples of classic rural Americana. The American Folk Art Museum’s latest exhibition, American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds, aims to capture the essence of this iconic symbol.

The new exhibition, set to run June 23 through January 2, 2022, will showcase an eclectic and unique selection of weathervanes from the late eighteenth to early twentieth centuries. Sourced primarily from private collections, these pieces offer unique insight into the history of American artistic form, as well as that of copper in the United States.

“Weathervanes have been a major part of the folk-art world for a very long time,” says Robert Shaw, curator of the exhibition and author of a companion publication which shares its name. “They have not been explored deeply or exhibited since 1981. There was this big niche hole that needed filling.”

That is exactly what the exhibition strives to do. With fifty vanes spanning over a hundred years of history, the pieces on display offer a unique historical perspective.

“I wanted a really diverse group, a lot of different forms,” explains Shaw. He placed extra focus on selecting pieces which would surprise those visiting the exhibition. “I wanted things that were unfamiliar, things people have never seen and have never been exhibited before.”

This approach resonates with current trends among weathervane collectors. “What I’m looking for, as any collector is now,” he says, “is a beautiful surface that shows a history of its use and the effects of weather, particularly with copper.”

Indeed, copper played an integral role in the history of weathervanes in America. The metal was commonly used among artisans from the colonial period onwards, with founding father Paul Revere even running a copper mill in one of his Massachusetts-based factories.

That availability meant that copper was commonly used in the creation of many things, weathervanes included. “Most of the vanes are copper,” Shaw explains, referring to the pieces in the exhibition.

It is easy to understand why. Known as a malleable metal, copper proved useful in constructing unique weathervanes featuring interesting forms. This workability, combined with its relative abundance, made copper the ideal material for craftspeople of the time.

Perhaps more important than these factors, however, was the beautiful look that is unique to copper. This is even more true for modern collectors. “When these things were originally made, copper was almost always gilded,” Shaw says. “It was the aesthetic that people wanted and expected, but after a few years out in the rain, snow, hail and sleet, the gilding starts to come off in bits and pieces. Then the copper hits the verdigris tone that it gets when not covered in paint or gilding.”

This unique appearance, difficult to replicate without the benefit of age and use, is a major drawing point for collectors. “They want that look of what it holds, the ancient look,” Shaw says. “They don’t want it bright and shiny.”

It is no surprise, then, that the pieces on display speak their history through their form. One of the best examples of this is a vane called Touring Car. Created by W.A. Snow Iron Works, one amongst a plethora of Boston metalworking companies that existed around the turn of the twentieth century, the piece spent most of its life being put to practical use.

Constructed in the early 1900’s, the vane depicts a contemporary automobile. As such, it sat for years atop an early gas convenience store in Lexington, Massachusetts. After the building’s demolition in the fifties, the piece was recovered and preserved. “Someone was smart enough to take the vane and save it,” explains Shaw. “It was held by a museum in Massachusetts, and they decided to sell it.” Since that time, it has been held in one of the premier private collections.

Touring Car is an apt example of the unique copper aesthetic to which Shaw refers. The aged color and trace gilding has an unmistakable, weathered look that speaks to its long history, as well as to the history of the material from which it was forged.

Church Banner weathervane by an unidentified artist. From Olde World

Church Banner weathervane by an unidentified artist. From Olde World Antiques, Inc.

Photograph courtesy of Ellen McDermott.

Another piece, titled Church Banner Weathervane and crafted by an unidentified artist, calls back to an even more distant past. “Banner weathervanes like this are basically long and rectangular, sort of flag shaped really,” Shaw says. “They relate back to medieval times when the lords of the castles in Europe would fly flags with their coat of arms on them.” The name of these flags, known then as fanes, serves as the etymological origin of vanes.

The style quickly made its way to the American colonies and later the United States, becoming especially common in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Generally found atop churches, these weathervanes often featured abstract and geometric forms.

“This one was made for a church in Orono, Maine in around 1830, we think,” Shaw explains, referring to Church Banner Weathervane. “It was on the church until maybe ten years ago. A dealer knew about it and made a deal with the church, and it was bought by a prominent private collector who was happy to lend it to us.”

While all the pieces on display offer fascinating historical insight, some are connected to American history in a more direct way. The exhibition’s oldest vane serves as the most tangible example of that. “The earliest one is of George Washington’s Dove of Peace,” Shaw says. “It was made for Mount Vernon in about 1787. It’s a pretty important piece historically for that connection.”

Like so many symbols of classic Americana, weathervanes have become less prominent with time. Today, they often serve as ornamental pieces, far removed from their former practical use.

Considering this, efforts such as the American Weathervanes exhibition take on a new relevance. Beyond simply displaying beautiful works of art, an admirable goal on its own, it also serves the important role of helping to preserve classic American craftsmanship in the public consciousness.

“Part of the appeal of these things is that they’re historical documents,” Shaw reflects. “They tell you a lot about what was going on in society, and there is a lot of context that can be brought to them.” As the first exhibition of its kind in roughly four decades, American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds seems primed to do just that.Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- The American Folk Art Museum Explores Weathervanes as a Symbol of Classic Americana

- The Monumental Legacy of Bronze Sculptor Seward Johnson

- Bronze Wings of the City Exhibit Tours America

- Scott Hemphill: In Service of Art

- Two Monumental Copper Sculptures Join Forces at Philadelphia Museum